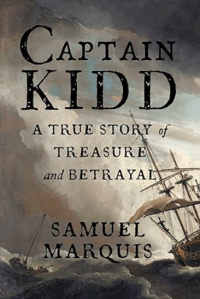

The True Story of Captain Kidd: An American

Hero and Antihero for the Ages

By Samuel Marquis

There comes a time in every rightly-constructed boy’s life when he has a raging desire to go somewhere and dig for hidden treasure.

—Mark Twain

My ninth-great-grandfather Captain William Kidd stands today as not only perhaps the most famous piratical plunderer of all time but the swashbuckler most responsible for the buried-treasure mythology that continues to fascinate historians, writers of all stripes, pirate aficionados, treasure hunters, and the general public. I have heard the passed-down family tales of my treasure-chest-burying-scoundrel of an ancestor since I first learned to walk, and although many of them have proven to be complete balderdash, they have made a lifelong impression on me. As Mark Twain understood, hidden treasure is a powerful allure for a young lad —and for that we can thank the “trusty and well-beloved Captain Kidd,” as he was celebrated by King William III of England in 1695 before being transformed into the “most notorious arch-Pyrate ever to sail the seven seas” a mere three years later. As British pirate scholar Patrick Pringle has written, it is unlikely that Captain Kidd “will ever be displaced as the Great Pirate.”

However, despite his villainous reputation, how much of an “arch-Pyrate” was Captain Kidd really and how much of our enduring fascination with both the man and myth can be chocked up to our love of roguish outlaw legends, deeply entrenched American folklore, and the supernatural? The answer is more surprising than one would imagine.

ΨΨΨ

A quick historical sketch tells us that Captain Kidd (1654-1701) was an educated man who could read and write and trace his roots to a common but respectable Protestant Christian family from Soham Parish, Cambridgeshire, England. Having gone away to sea at an early age as an apprentice or cabin boy from the port town of Dundee, Scotland, he possessed ample nautical skills developed from the hard experience of a life at sea and thorough training in mathematics and navigation. He also had a little salty roguishness in him from spending two decades in the Americas from the mid-1670s through the 1680s sailing, fighting, and drinking with rowdy, violent, and vulgar buccaneers and merchant seamen. Whether he did in fact serve under the most famous buccaneer of all time, Sir Henry Morgan (1635–1688), remains unknown, but there is no doubt that William Kidd was a patriotic English privateer during his twenties and early thirties, sticking it to imperial Spain with the fate of the two bellicose empires hanging in the balance.

In his era, the early Age of Enlightenment (1685-1815) and middle Golden Age of Piracy (1650-1730), Kidd was a respectable privateer not a pirate, meaning his activities were sanctioned by the English government through a “letter of marque,” a license authorizing him to legally attack, capture, and plunder enemy ships in wartime. Yet, like many sea rovers in his day, his ultimate fate, as well as his perch in history, would depend on the not always clear distinction between legal privateer and outlaw pirate. Privateering as a seafaring profession for both patriotism and profit has existed at least as far back as the Roman Republic, and privateering ships and the privateersmen who manned them (both are referred to as “privateers”) served the function of an auxiliary, cost-free navy that were recruited, commissioned, and unleashed upon the enemy when the resources of combatant European nations were overextended.

While the Anglo-American, Dutch, and French buccaneers of the seventeenth century Caribbean were most certainly ruffianly and profligate, they were licensed privateers not renegade pirates, and Kidd lawfully plundered the Spanish on land and by sea in the Gulf of Mexico and West Indies to weaken Spain’s grip in the New World. The buccaneers’ lifestyle was built upon a modern-like, egalitarian political framework. Their homegrown system of direct democracy resulted in a unique brotherhood defined by honor, trust, integrity, and lending a helping hand to those in need. It played a huge role in nurturing Kidd’s core democratic value system and generosity. During his seafaring career, he went out of his way to help the unfortunate and he employed African Americans, Native Americans, East Indians, and Jews as share-earning stakeholders aboard his privateering ships-of-force, making him rather progressive and tolerant compared to the vast majority of his contemporaries.

In 1688, Kidd made New York his home port and bought valuable waterfront property in the city, and from July 1689 through April 1698 he fought as a licensed privateer in King William’s War against France (1689-1697), following William and Mary’s seizure of the English throne in the Glorious Revolution to ensure a Protestant succession. By May of 1691, he was a bona fide New York war hero, gentleman, and man of affairs married to the most dazzling socialite in town: the twice-widowed, twenty-year-old Sarah Bradley Cox Oort. With his “lovely and accomplished” wife Sarah, the wealthy New York privateer and merchant ship captain, jury foreman, and model citizen would have two daughters, Elizabeth and little Sarah, and in 1695 he was recruited by a group of wealthy London investors to lead an expedition to the Indian Ocean to battle the French and hunt down freebooters as King William III’s lawfully licensed privateer.

The plan was for Kidd to hunt down the Euro-American pirates of Madagascar, legally seize their ill-gotten riches, and keep them for not only himself and his privateering crew but for the king and lordly sponsors from the powerful Whig party that dominated the English government. Among Kidd’s wealthy London financial backers was Lord Bellomont, a powerful Whig House of Commons member and soon-to-be royal governor of New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. Kidd was to capture the “predators of the seas” and their freshly plundered riches after they had raided the royal treasure fleets of the Great Mughal and other East Indian shipping between the Malabar Coast of India and Mocha and Jeddah in the Red Sea. Based on the New York privateer’s sterling reputation, the investment group not only issued “the trusty and well-beloved Captain Kidd” two special government licenses but built a 34-gun warship, the Adventure Galley, to his specifications.

Unfortunately for Kidd, his nearly three-year-long voyage turned out to be an epic disaster and turned him overnight into one of the most notorious criminals of all time. His great misfortune was that he had followed in the wake of the English pirate Henry Every, who had pillaged the Great Mughal’s fleet and encouraged the mass rape of the Muslim women aboard one of the plundered ships. A year into the expedition to the far side of the world shortly after Every’s debauchery, Kidd and his crew had still not encountered a single enemy French or pirate ship that could be seized as a legitimate prize and they had suffered one disaster after another, including raging storms, a tropical disease outbreak, severe thirst and starvation, and repeated attacks by the East India Company, Portuguese, and Moors (Muslim East Indians). Increasingly desperate to earn some money under their standard “no prey, no pay” privateering contract, a large number of his New York and New England seamen wanted to become full-fledged pirates themselves and plunder the ships of all nations to garner the prodigious riches of the East. However, the law-abiding Captain Kidd would not allow any violations of his two legal Crown commissions, one to fight the French and the other to hunt down pirates.

During the grueling voyage, Kidd accidentally killed his unruly gunner, William Moore, a man with two prison sentences to his name, by smacking him in the head with a wooden bucket while quelling a mutiny; and he lawfully seized two Moorish ships, the Rouparelle and Quedagh Merchant, that presented authentic French passports and carried gold, silver, silks, opium, and other riches of the East. However, while these wartime seizures were 100% lawful and he never once himself committed piracy in India, he soon thereafter looked the other way during the capture of a Portuguese merchant galliot that presented official papers of a nation friendly to England. His seamen sailing separately from his 34-gun Adventure Galley in the captured Rouparelle seized from the Portuguese vessel two small chests of opium, four small bales of silk, 60 to 70 bags of rice, and some butter, wax, and iron. Though a measly haul, the act technically constituted piracy even though Kidd wasn’t directly involved in the capture. He only allowed the seizure to pacify his mutinous crew, who had by this time divided into “pirate” and “non-pirate” factions aboard his three separate privateering ships; and in reprisal for the damage inflicted upon the Adventure Galley and severe injuries sustained by a dozen of his crewmen from two Portuguese men-of-war that had attacked him without provocation months earlier.

Despite the countless challenges he faced during his perilous voyage and a second full-scale mutiny because he refused to go all-in on piracy, Kidd miraculously made it back to the American colonies from Madagascar with around £40,000 ($14,000,000 today) of treasure in his hold and the French passports that proved he had taken the Rouparelle and Quedagh Merchant legally in accordance with his commission. However, when he and his small band of loyalists reached Antigua on April 2, 1699, they received heartbreaking news. The Crown, at the urging of the East India Company, had sent an alarm to the colonies in late November 1698 declaring them pirates and ordering an all-out manhunt to capture and bring them to justice. With the Englishman Henry Every and most of his plundering, gang-raping outlaws still at large, Captain Kidd was now Public Enemy #1 in the world.

He decided to try to present his case for his innocence and obtain a pardon from his lead sponsor in the voyage, Lord Bellomont, who had by this time taken office as the royal governor of New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. After burying a portion of his legally obtained treasure on Gardiner’s Island in Long Island Sound and distributing a number of goods to several trusted community leaders and seafaring friends as a precautionary measure, Kidd sailed into Boston on July 3, 1699, to meet with Bellomont, who had promised him a full pardon. But with Kidd now a wanted criminal and Every still at large, Bellomont and the other London backers, members of the once powerful Whig Junto that had fallen from power to the spiteful Tories, wanted nothing to do with the scandal. Having merely lured his business partner into Boston by dangling the possibility of clemency before him, Bellomont treated Kidd with suspicion and arrested him and his loyal seamen shortly after their arrival to port.

After being stripped of all his lawfully seized plunder and enduring six months of incarceration in Boston, Kidd was shipped to England to stand trial. Abandoned by his wealthy Whig sponsors who had been supplanted by the revitalized Tories, he was found guilty and hung in public shame on May 23, 1701, where he proclaimed his innocence before a drunken, jeering mob of Londoners. Days later, his corpse was coated with tar and hoisted in a gibbeted iron cage downriver at Tilbury Point near the mouth of the Thames, where it would remain for the next twenty years to serve as the English State’s grisly warning to other would-be pirates of the fate that awaited them if they dared threaten England’s valuable trade relations with India by pursuing the short but merry life of a pillaging freebooter.

ΨΨΨ

The question of Captain Kidd’s guilt or innocence has been hotly debated by historians and the reading public ever since his gruesome public hanging. However, it is important to bear in mind that Captain Kidd was not a 100% innocent man. Even by the sketchy standards of the early Age of Enlightenment, he was guilty of at least one act of piracy during his Indian Ocean expedition, or at least of failure to lift a finger to prevent his crew from committing piracy in the taking of the Portuguese galliot; and, possibly but not definitively, one count of manslaughter in a fit of passionate rage against his mutinous gunner William Moore, who had two prison sentences to his name, one for striking his captain, before sailing with Kidd.

At the same time, although Kidd was not a fully innocent man by the legal standards of his age, he was most certainly no pirate like Henry Every, which is an ironic twist that many people find hard to reconcile for the man who has been called “the most famous pirate of all time.” As one historian has put it, “His innate respect for order, his sense of duty and mission, his past life as an honest, successful seaman, as faithful husband and loving father, and above all, his ambition for the future—all these factors precluded Kidd from ever becoming a true pirate. If he committed piracies, they were acts of expediency, even acts of survival.” Thus, the most famous “arch-Pyrate” of all time was no outlaw pirate in temperament, inclination, or practice. Contrary to our embellished tropes over the centuries with characters like Long John Silver, Captain Hook, Captain Blood, Captain Jack Sparrow, and rocker Keith Richard’s as Captain Teague, the father of Sparrow, Captain Kidd never forced anyone to walk the plank, swilled rum with treasure chests overflowing with gold, silver, and jewels at his feet, or roared catchy pirate phrases like “Arrgh!” or “Shiver me timbers!” or “Dead men tell no tales!”

The real Captain Kidd was simply a bold adventurer at the wrong place at the precisely the wrong time in the wake of the Henry Every debacle. But even more critical to his ultimate fate, he was backed by the worst kind of sponsors imaginable. Not only did the Machiavellian Lord Bellomont coerce him into leading a virtually impossible expedition to the Indian Ocean to hunt down pirates, by threatening to seize his crew and ship in 1695 when Kidd initially turned down the command of the voyage, he and his fellow Whig noblemen dropped him as soon as he became a potential liability. Though these unspeakably powerful leaders gave the pirate-hunter firm, up-front assurances that they would stand by him in his difficult mission, they threw him overboard like ballast at the first whisper of trouble to protect their lordly reputations.

Unlike the largely unknown real pirate Henry Every, Captain Kidd’s story has been told and retold in thousands of accounts, from the heavily biased broadsheet newspapers and ballads of his day, to the countless books and journal articles produced over the past five centuries, to the Hollywood swashbuckler films of the silver screen during the past century. And yet, the tale of this humble-born New York privateer—who rose up by his own bootstraps to become the “trusty and well-beloved Captain William Kidd” of the King of England himself—has been lost to us in a foggy haze of legend, myth, and propaganda for the past four centuries.

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” proclaimed fictional reporter Maxwell Scott in the classic 1962 Western film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directed by John Ford. But when it comes to my ancestor Captain Kidd, such an approach cannot suffice. For the simple truth is there was an actual flesh-and-blood Captain Kidd, and the story of that Kidd, my real ninth-great-grandfather, is far more fascinating, nuanced, action-packed, and ultimately tragic than the caricature of mythology and pop culture.

Few historical figures have cropped up at so many important turning points on the global stage, come into contact with so many historically noteworthy individuals in such a short period of time, have seemed to be everywhere at once, had more lies spread about them in their own lifetime, or cast such a long shadow for five consecutive centuries and counting. Case in point: Kidd’s trial was the greatest courtroom drama of the eighteenth century, and one of the biggest political scandals in British-American history, rocking the New World and the Old and threatening “to tip the subcontinent of India to the Maharajahs.” But it was nothing but a sham proceeding to make sure Captain Kidd hung for the crimes of Henry Every and the other real Red Sea pirates of the 1690s.

But once we peel away the onion layers of mythology and propaganda to uncover and illuminate the real Captain Kidd, as judged by the moral standards of his era, we realize that he was a good, honest, and courageous man given an impossible mission and sponsored by dirty, rotten scoundrels who threw him to the wolves. Thus, at the end of the day, the supreme irony at the heart of Captain Kidd saga is that the man widely considered “the greatest pirate of all time” was no pirate at all. Behind the Kidd myth was a real man: a son, a husband, a father woven into the tapestry of early America, rendering him for all the ages a unique yet flawed colonial American hero (or perhaps better anti-hero), whose life story by a simple twist of fate happened to be fascinating, exciting, bizarre, and heart-rending enough that Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Robert Louis Stevenson have all made him immortal in their most celebrated works.

It is for this reason that the legendary Captain Kidd has had the last laugh on us all.

About Sam:

© 2025- Ronovan Hester Copyright reserved. The author asserts his moral and legal rights over this work.